Most little kids at one point or another consider the career path of being a fireman. Little do they know that firemen use chemistry every day in their work. What follows below is a description of how firemen fight fire and how it relates to the chemistry of combustion.

There are 4 main methods for stopping a combustion reaction (putting out a fire):

- Smothering

- Starvation

- Cooling

- Breaking the Chain Reaction

Smothering

As mentioned earlier the key ingredient in a combustion reaction is oxygen. By placing an object over a fire that allows no oxygen to enter the combustion area, the fire will quickly run out of fuel and die.

A good example of this is a kitchen grease fire. For those of you that cook, you should know that you never try to put out a grease fire with water (H2O). Why not?

The answer to this is in the formula of water itself. Water contains oxygen. If the fire is hot enough (which grease fires often are), the water, rather than putting the fire out, vaporizes into flammable gases that actually provide fuel in the form of oxygen and hydrogen gas molecules. For this reason, the best way to put out a kitchen grease fire is to place a lid over the pot or pan on fire and cut off the oxygen to the blaze.

Putting out kitchen grease fires

ABC 2 News - WMAR (YouTube)

Starving

Fire break

One of the other key ingredients to a combustion reaction is the fuel or hydrocarbon molecules (molecules made up of hydrogen and carbon like octane) in the combustion reaction. One of the best ways to stop a fire from spreading or starting in the first place is to remove the fuel. In an active fire this means removing any flammable materials from its path. Firemen do this in forest fires by cutting trenches called "fire breaks" that are devoid of plants or other organic materials. Before a fire starts this would mean removing any flammable materials or putting a non-flammable space between combustible materials and the population.

Southern Alberta Wild Fire near Lethbridge November 27, 2011

bigsky780 (YouTube)

Cooling

In fires that burn at lower temperatures than a grease fire, water in sufficient amounts will extinguish the flame. This process is called cooling and essentially extinguishes the fire by removing the "spark" necessary to keep the reaction going. The cooling of the temperature lowers the overall energy of the reaction until it cannot make it over the activation barrier.

Breaking the Chain Reaction

Many fire extinguishers use chemical compound powders like sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, baking soda), potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3, nearly identical to baking soda), or monoammonium phosphate ((NH4)H2PO4, shown above).

These chemicals work by creating a non-flammable coating on the surface of the area on fire and breaking the chain reaction of the fire. This is actually another way of starving the fire since the coating essentially removes the fuel from the path of the fire.

So now we know how a fire works chemically and how to extinguish a fire by combating those properties that make it burn, but how do we distinguish arson from other forms of fire?

Arson

Arson is the criminal setting of a fire to commit at least vandalism and at worst murder or even mass murder. Arson is difficult to investigate for three main reasons:

- The arsonist can plan out the arson well in advance and bring all the tools needed to commit the act with him/her.

- The arsonist does not need to be present at the time of the act.

- The fire itself destroys evidence tying the arsonist to the crime.

Investigating arson is therefore limited to finding the chemicals left at the scene and identifying them as well as reconstructing the path the fire took to find areas of ignition and patterns in the arsonist's methods.

To determine if a fire has been started by an arsonist, the arson investigator needs to begin examining a fire scene for signs of arson as soon as the fire has been extinguished. Looking for accelerants is the first step. The presence of residues in the soot left by petroleum based accelerants can be a dead giveaway that an arson has been committed.

Accelerant burn patter on concrete floor

The search of the fire scene must focus on finding the fire�s origin, which may be most productive in any search for an accelerant or ignition device. How the fire started gives the best indication as to whether the fire was accidental or intended.

Some common signs of arson include:

- Evidence of multiple sites of ignition

- Lines of accelerant residue indicating it was poured from space to space in the structure

- The majority of the burning taking place at the floor rather than the ceiling. (Heat rises so naturally fire does too but if there is a lot of accelerant on the floor the majority of the burning will take place there)

- The presence of unburned combustible liquids (these are rarely completely consumed in the fire)

Collecting Evidence of Arson

Starting at the location suspectedto be the origin of the fire, the ash, soot and any other porous materials should be collected and stored in airtight containers. These materials are the most likely to contain left over/unburned accelerant.

A vapor detector (sniffer) can be used to collect and identify vapors from the burned areas of the fire.

Hand held Vapor Detector

Samples of various burned materials should also be collected throughout the burned area for later analysis. How thoroughly materials burn can tell the arson investigator a lot about the accelerant(s) used as not all accelerants burn at the same temperature.

Finally, the investigators look for obvious ignition devices like matches, electronic ignitors or even the glass of a "Molotov cocktail".

"Molotov Cocktail"

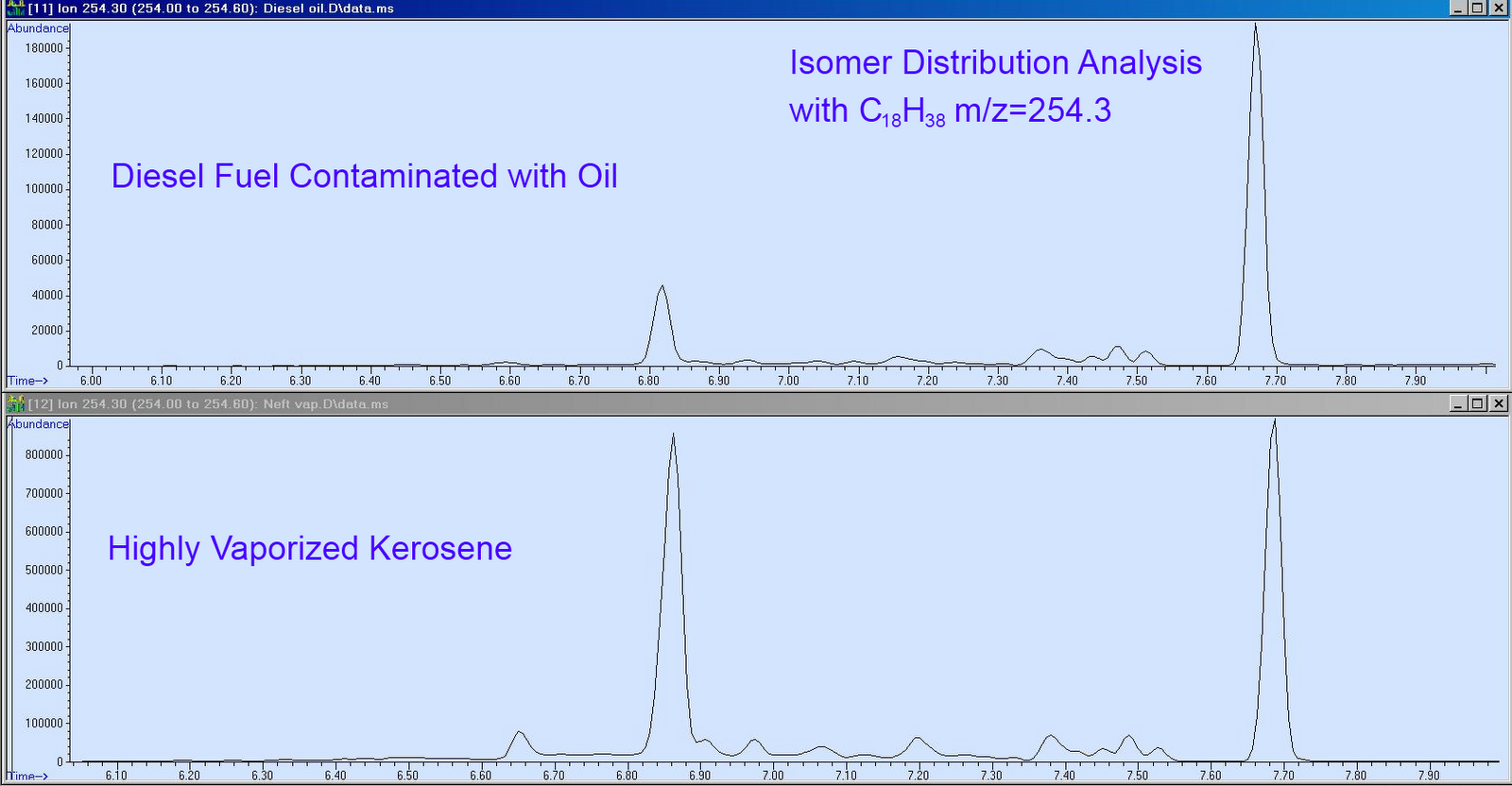

Once collected the most common method for identifying the accelerants at a fire is by the use of a GC (Gas Chromatograph) or GCMS (Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometer). The gas chromatograph is the most sensitive and reliable instrument for detecting and characterizing flammable residues. Most arsons are started by accelerants such as gasoline and kerosene. Gas chromatography can separate the hydrocarbon components and assign a unique patterned graphic for each product type.

Chromatograms of various accelerants

By analyzing the gas chromatographic peaks from evidence recovered from fire-scene debris and comparing it to reference chromatogram of known flammable liquids, the arson investigator can identify the accelerant used to start the fire.

GC Reference and Arson Samples Containing Turpentine