The content that follows is the substance of lecture 13. In this lecture we cover Precipitation Reactions and Acid-Base Reactions.

Continuing the discussion of what makes a reaction proceed to product, we now return to the formation of a solid. In a reaction in which one of the products has little to no solubility (ability to dissolve) in water, a solid will form. This solid is referred to as a precipitate. This is because much like rain falls from the sky, the solid that forms will fall out of the solution to gather at the bottom of the container it is in.

The trick to understanding a precipitation reaction is knowing which compounds that form are not soluble. Unfortunately the only way to know is to memorize some solubility rules:

The table above will be the few rules that you are expected to memorize. Note that there are exceptions to most of the rules. You will need to know these as well.

Typical questions regarding a precipitation reaction will require the identification of the Net Ionic Equation which we covered previously or will be a simple question asking that you complete a reaction and determine if it will make product or not. In other words will it form any compounds that drive the reaction in the forward direction.

Here is an example:

What are the products for the following reaction?

AgNO3(aq) + KI(aq) → ?

In order to answer the question you must realize that this is a Metathesis reaction. This is a fancy word for "swapping partners" as a reaction.

The best way to complete this process and correctly predict the products is to take each of the reactants apart into their ions:

Ag+ + NO3- + K+ + I-→

Now swap the positive ions and make the new compounds being sure to balance the charges so that the compound is neutral.

Ag+ + NO3- + K+ + I-→ AgI(s) + KNO3(aq)

Identification of AgI as a solid comes from the exceptions to the rules for halides in the table above.

The net ionic equation for this reaction will only involve those ions that form the solid so:

Ag+(aq) + I-(aq) → AgI(s)

In order to practice these reactions you need to spend some time first working with the rules and then use the questions below to test yourself.

Now on to the second part of this reactions lecture....

As we saw when we were working on nomenclature, acids can be identified by the way their formula is written with the ionizable hydrogens at the front of the molecule: HCl, H2SO4 etc. An acid is defined by its ability to donate this hydrogen (also called a proton) when it is in aqueous solution. Bases on the other hand are generally recognizable by the presence of a hydroxide ion in their formula: NaOH, Ba(OH)2 etc. We define a base by its ability to absorb protons from solution.

So now that we know what they are, what do we do with them? Well, whenever an acid and a hydroxide base are reacted together they always produce the same two types of products: a salt and water.

Example: HCl(aq) + NaOH(aq) → NaCl(aq) + H2O(l)

NaCl is the salt is this reaction and you already know water. If we look at the net ionic equation for this reaction it shows that the driving force for the reaction is the production of water:

H+(aq) + OH-(aq)→ H2O(l)

When you react the acid and base, this process is called neutralization. This is because the products of the reaction do not contribute any protons or hydroxide ions to the solution beyond the normal dissociation of water in water which is a very small amount (Dissociation constant Kw = 1.0x 10-14 ). The concentration of H+ based on this dissociation is 1.0 x 10-7M and when we take the pH of this value (-log(1.0 x 10-7)) it equals 7 which is defined as neutral pH.

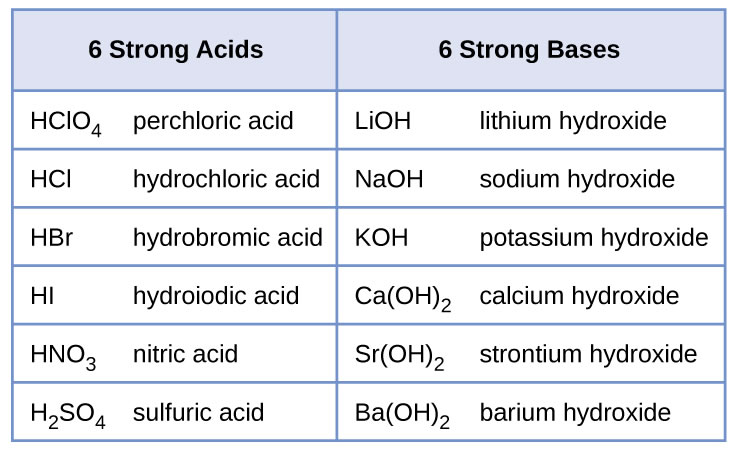

For now we will concentrate on the reactions of strong acids and bases. The table below contains the strong acids and bases you need to know. All other acids and bases will be considered weak for the purpose of this course.

Here are some practice problems for the reactions of acids and bases: